During the Cold War, perceived threats to civilian populations in the form of enemy attacks and environmental concerns prompted the organization of Civil Defence plans for cities across North America.

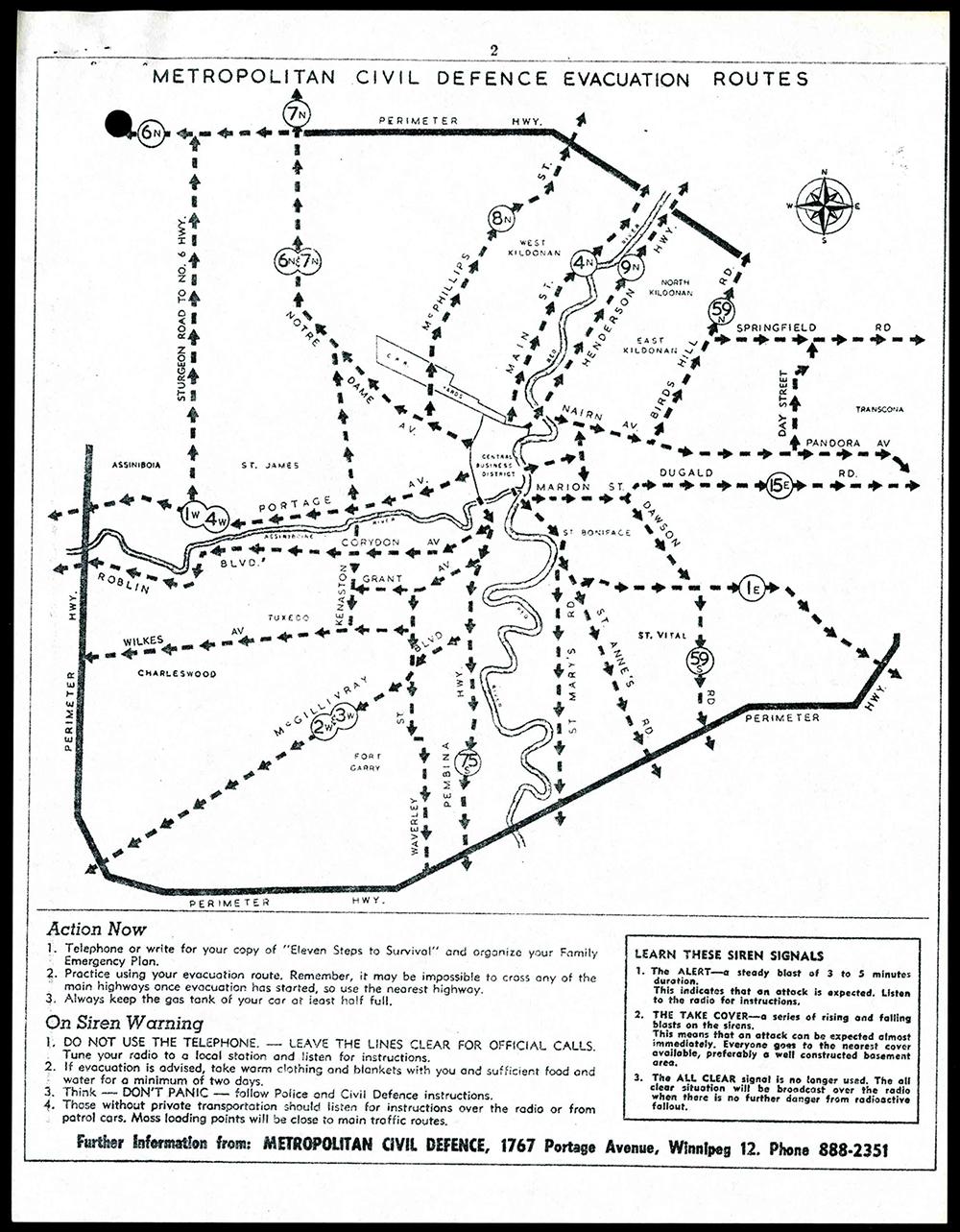

Because Winnipeg was a major urban center, Civil Defence authorities in Canada considered the city a potential target for enemies in wartime. As such, planning efforts focused on how to safely and effectively evacuate the City and build capacity in outlying areas to assist evacuees with medical care, accommodations, and other services. A radio tower and shelter were also positioned at Headingley to support emergency communication needs.

“It’s not surprising that Winnipeg adopted a Civil Defence strategy and did so earlier than other Canadian cities,” said Sarah Ramsden, Senior Archivist at the City of Winnipeg.

In the Greater Winnipeg area, these efforts were led by the Metropolitan Civil Defence Board and later the Metropolitan Corporation of Greater Winnipeg.

“While the idea of Winnipeg being a target for a nuclear attack might seem far-fetched from our perspective, to people who experienced the Second World War and the Cuban Missile Crisis, this threat was serious,” said Ramsden.

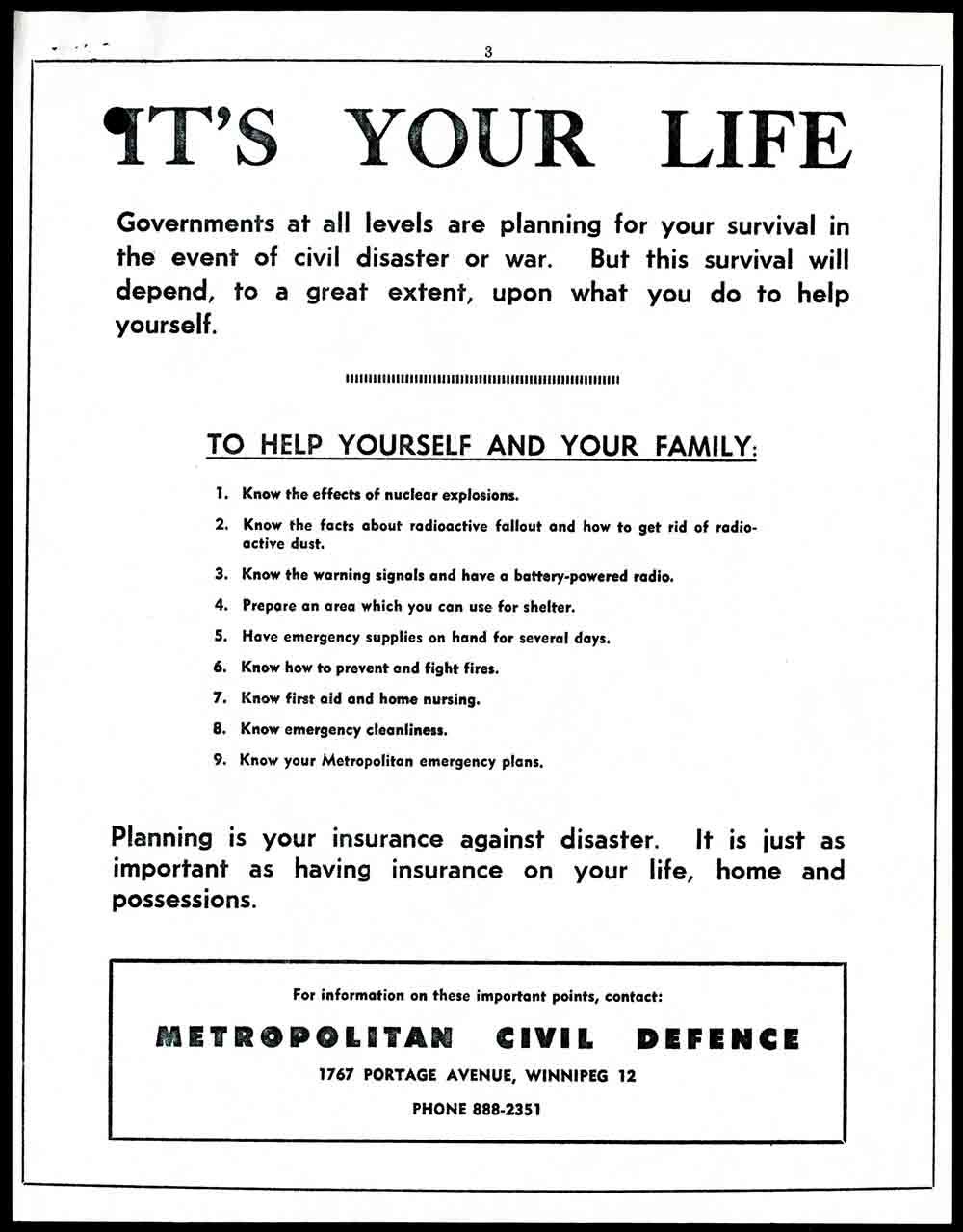

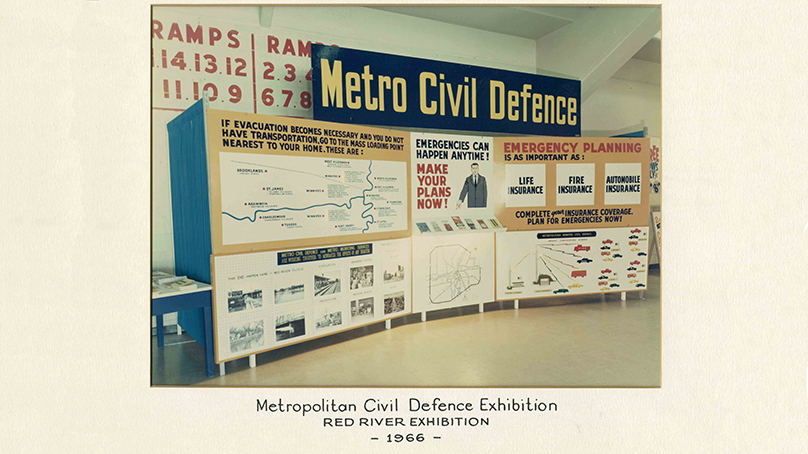

In addition to coordinating local government services and strengthening infrastructure to deal with emergencies, officials conducted training programs, exercises, and presentations across the Greater Winnipeg area. Their messages encouraged the public to maintain “a constant state of readiness.”

In case of evacuation, radio announcements and exhibitions instructed people to plan ahead – this meant keeping their vehicles gassed and ready or locating the nearest mass loading point for transportation to a safe area.

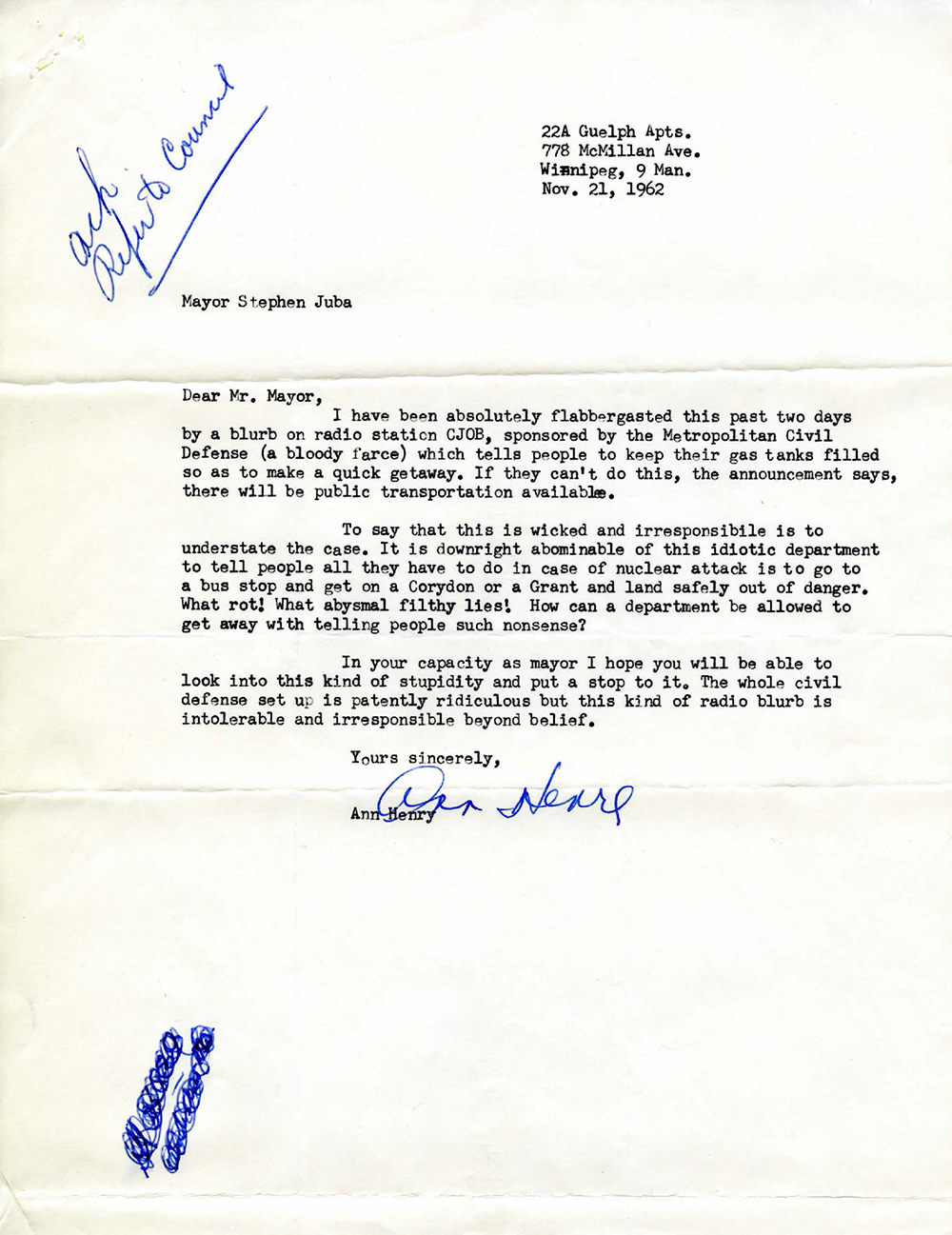

Critics of Civil Defence were quick to point out the flaws in such plans. In a strongly-worded letter to Mayor Stephen Juba, one citizen confessed to being “flabbergasted” – citing the absurdity of escaping a nuclear attack via public transportation and her displeasure with Civil Defence in general, she called on the Mayor to end the program.

Over time, the threat of nuclear warfare receded. However, the potential for floods, disease epidemics, hazardous events, and other disasters still remained. Emergency planning shifted focus, with Civil Defence evolving into emergency measures programs. The Civil Defence Act passed in 1952 was amended and changed, but never repealed.

“This threat, which felt very really to people, eventually passed,” said Ramsden. “Winnipeg acknowledged the threat, responded, and then applied what was learned to other situations. We can take some comfort in knowing what we as a city have been through.”

Today, the City’s Office of Emergency Management (OEM) is committed to supporting the resiliency of all Winnipeg residents, by supporting preparedness for emergencies and disasters, mitigating and coordinating responses to emergencies and disasters, and aiding in recovery efforts.

OEM manages the Emergency Operations Centre, an emergency space used to coordinate efforts in response to an ongoing incident, emergency or disaster.